Lawyer Autonomy and You're Not the Boss of Me-ism

/Lawyers tend to prefer working alone. Many don’t enjoy being managed. That’s fine. To each his own. The desire for independence is neither good nor bad. There are times when it’s a valuable and necessary trait. But when law firm partners choose autonomy over the health of their law firms, they are not qualified to be owners. The desire for complete autonomy is one of the most insidious and corrosive elements impacting law firm cultures. This isn’t new. What’s changed is the appetite of other partners to tolerate it.

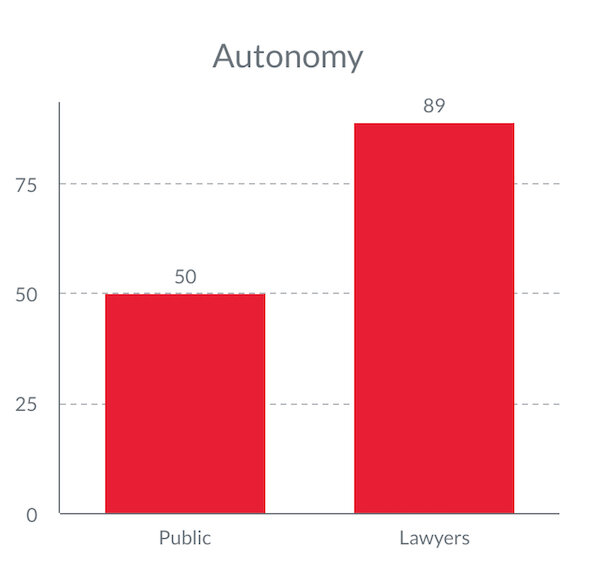

It’s commonly understood that lawyers are different. Dr. Larry Richard has written extensively about lawyer personalities and we won’t try to improve upon his work here. Read this. And this. And this. While there are a number of differences between lawyer personalities and the general public, our focus is on autonomy. Lawyers are in the 89th percentile in preference for autonomy, compared to the 50th percentile for everyone else. What does that mean? According to the Cambridge Dictionary, autonomy is “the ability to make your own decisions without being controlled by anyone else.”

If a lawyer’s desire for autonomy is so strong that he simply will not accept any input or intrusion into his practice focus, client selection, prices, methods and tools of practice, business operations, or communication style, there’s a perfect answer: hang a shingle and run a solo law firm. Over time, hire more people and dictate how things will run. It’s that simple.

From “Herding Cats: The Lawyer Personality Revealed,” © Dr. Larry Richard, LawyerBrain℠

Not surprisingly, roughly 63% of the 1.3 million active lawyers in private practice in the US are solos or in firms with fewer than 5 lawyers (here). Nearly 87% of private practice lawyers in the UK are solos or in firms with fewer than 5 lawyers (here). And 86% of Australian private practice lawyers are solos or in firms with fewer than 5 lawyers (here). So… problem solved? The remaining private practice lawyers working in larger firms have accepted the necessity and mutual benefits of centralized governance? Not even close.

Many lawyers are risk averse, so they come together for the specific purpose of sharing risk, to share overhead, to combine forces so that when one practice is up and another is down, earnings are smooth. And when these practices trade places, earnings remain smooth. Lawyers who choose to join forces to mitigate their risk forgo complete autonomy. Their individual success is linked to the firm’s success. Law firm partners as owners of the business have a personal, professional, and fiduciary obligation to act in ways that benefit the greater good of the organization. Yet many partners act selfishly, putting the needs of the firm far below their personal preferences.

Biglaw culture generally allows for partners, particularly those close to key clients or billables, to set their own course. They’re allowed to substitute their own preferences or peccadillos for sound business decisions. An inclusive and flexible culture can accommodate one partner’s quirky affectation for tweed jackets and high tops or another partner’s demand for a Mac laptop. But law firms struggling to find their way in a changing marketplace can no longer tolerate partners whose demands to be left alone and unmanaged hurt the enterprise.

There are obvious ways in which unbridled autonomy can be harmful. There are also numerous non-obvious ways. Let’s explore a few ways in which partners reveal themselves to be individual contributors in disguise.

Hoarding. Some partners like to do the work themselves rather than delegate. This is harmful in the short run because leverage (aka delegation) generates profits, and in the long run because charging partner rates while competitors charge associate rates places the firm at a distinct competitive disadvantage. A partner who claims to be a perfectionist, who can’t trust others to do the work properly, has acknowledged an inability to train or mentor, which is a critical contribution of a business owner.

Working alone. Owners focus on growing the business for everyone, for today and tomorrow. Individual contributors focus on their personal productivity. Collaboration is a critical driver of growth, whether in delivering legal work or in pursuing business development opportunities. Owners work and hunt in packs. Individual contributors work and hunt alone.

Withholding credit. Owners adopt a bounty perspective: How many colleagues can I involve to ensure this will be a successful effort? Individual contributors adopt a scarcity perspective: How can I retain all credit for my personal contribution, even if it means losing some opportunities where I would have to share credit?

Failure to cross-sell. Owners view clients as the firm’s clients, and constantly seek to proactively broaden the scope and depth of client relationships. Individual contributors jealously guard key client relationships, refuse to share contacts or use the firm’s CRM system, and limit opportunities to identify or address client needs outside their personal area of expertise.

Over-pricing/over-billing. Owners recognize that long-term profitability is a function of satisfied clients, and sometimes this means pricing for the long-run rather than pricing for immediate profits. Individual contributors bill as much as they can and collect as much as they can, even at the risk of alienating clients.

Under-pricing/under-billing. In a price-sensitive market, lowering rates (or slowing the pace of rate increases) can be an appropriate tactic to remain price competitive. But self-serving partners proactively and unnecessarily offer rate discounts in every pitch, write down others’ time on a pre-bill while preserving their own time entries, offer discounts as the solution to every client issue, or offer invoice write-downs rather than pursuing the collection of aged receivables. The result is that all partners share in the profit dilution while the individual benefits from increased compensation. Owners seek to earn the highest rewards primarily by boosting the firm’s financial performance.

Resist re-engineering. Owners are constantly seeking a competitive advantage, and embrace a culture of continuous improvement. They ask: How can we use our deep expertise to deliver higher quality, faster throughput, greater client satisfaction, and improved firm profits? Individual contributors resolutely stick to their preferred approach, even if their approach is inconsistent with how others deliver the same work, or with how clients want the work done, believing that their “artistic license” takes precedence over consistency and quality.

Poor fiscal hygiene. Owners record their time, review and issue invoices, and collect their fees, all on a timely basis. They manage client expectations proactively by using matter budgets and proactively communicating scope changes. Individual contributors submit incomplete and tardy time sheets, provide incomplete and ambiguous task descriptions that lend themselves to client review, delay the review of pre-bills, send invoices long after the work is done, and when the client inevitably pushes back they discount heavily because they’re rewarded for cash in the door.

In the face of a game-changing pandemic, on top of the wholesale revolution taking place in the legal marketplace, law firm leaders and partner-owners can’t and shouldn’t be required to afford the luxury of subsidizing the whims of partners who are unable or unwilling to do what’s best for the firm. Those who act selfishly are individual contributors — quite possibly highly-compensated individual contributors because what they offer has market value. But they have revealed themselves as unqualified to be owners of the business. Their contribution, while valuable, needs to be managed and rewarded appropriately.

Inaction is costly. Selfish partners dilute profits, alienate clients, impair morale, and hold back the firm competitively. Addressing it can be thorny, but the payoff can be meaningful. The action plan is simple:

Identify what it means to be a partner of your firm. While it may sound new agey, this is about establishing a clear code of conduct for the business. It’s critical for the business owners to declare the behaviors they expect of each other and how they’ll hold themselves accountable. It’s not enough to post the values on the wall. It’s important for the owners to live these values every day, from the top down, without exception.

Measure profit and client satisfaction. Profit is obviously a desirable financial objective, but it’s also a decent proxy for long-term client satisfaction. Sustainable profit comes from delivering what clients want, in the way clients want it, at prices the market is willing to pay. Measuring inputs, or units of partner productivity, even top-line revenue, isn’t enough. We have to measure outcomes, including profit and client satisfaction.

Review and update the partner compensation plan. If partners have the choice between acting in their own self-interest or doing what’s right for the firm, then management hasn’t done its job. It’s the responsibility of management to align what’s good for the partner with what’s good for the partnership. Many of the individual behaviors cited above happen because the compensation plan specifically rewards them. Many of those implicated aren’t bad actors; they’re just doing what management must believe is important, since the compensation plan and/or operating agreement allow it. Management must remove choices by aligning partner rewards with the firm’s strategic priorities.

Many law firms were already facing an uncertain future before the recent and existential threats of a global pandemic and looming recession. In uncertain times, leaders must take bold action. Let’s get started.

Timothy B. Corcoran is principal of Corcoran Consulting Group, with offices in New York, Charlottesville, and Sydney, and a global client base. He’s a Trustee and Fellow of the College of Law Practice Management, an American Lawyer Fellow, and a member of the Hall of Fame and past president of the Legal Marketing Association. A former CEO, Tim guides law firm and law department leaders through the profitable disruption of outdated business models. A sought-after speaker and writer, he also authors Corcoran’s Business of Law blog. Tim can be reached at Tim@BringInTim.com and +1.609.557.7311.